I have an artistic concern today, one brought about by the publicity for the "Lost" tv finale: do the desires of an audience undermine the quality of long-form stories in tv and film series? Other ways of looking at this question are: do tv series and film franchises have to get worse over the years? Is it necessary that ideas run out of steam, or is it a matter of poor execution or complacency? Do some story-tellers just promise more than they can give?

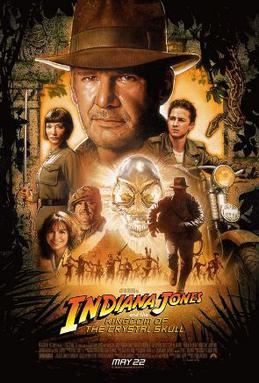

Wanna learn anything about this unearthly object? Tough - it's just a stupid plot device.

There are many variations on the relationship between an artist and the public, but it's an important dynamic, and I like to consider these topics. I tried to move further away from "Lost," so I could think about the issues rather than one silly show... My thought gave birth to still more questions, like: do demands for fan-gratification - through resolution and/or clarification - mean that repetition is the real problem? Is it worse nowadays, since more of the audience participates? What does this say about the dialogue between artist and spectator?

In looking at this problem, it made the most sense to confine myself to film and television. Although I might use some examples from literature, turning to books at the moment would simply complicate the discussion too much. It would also digress from what this site is about. In the end, film and tv are easier to discuss because of their popularity, their ease of access.

Throughout, I keep going back to the factors that affect audience and artist, sometimes repeatedly turning to the same issues. Sometimes I go to them repeatedly. I really hope this doesn't get too boring for anyone who reads this. At least no one could ever claim I didn't "write enough" over a two-week gap...

The Modern Age: Your Best Fans, Your Worst Enemies

As methods of story-telling, film and television series have a potentially unhealthy relationship with the internet's ability to generate high volumes of critique and criticism. At times, it's beneficial - the attention of devotees might be the sole cause for a show renewal or green-lighting a film.

It's true that complaining viewers might help steer a series from impending disaster. In the past, this merely happened through reduced ratings and letter-writing. The new forum of the internet provides a huge array of commentators, however. The problem is the same as before - some fans don't have good or selfless or thoughtful taste... Some are stingy and don't like thinking too hard, some are boring and focus on things that few notice, while others are so intelligent that everything seems moronic to them.

In any era, most people who voice their opinions, making an actual effort to address a complaint about some piece of art, have no training in artistic principles, and a small minority write more from idleness than interest. If a particular piece of art doesn't have to be "perfect" - if it can make bad choices, artistic or otherwise, over time - then there's a danger in listening to all those voices. In fact, there's a danger in listening to almost all of them.

An audience can focus on unimportant details, though. And when a vocal group of fans make unfair demands on a serialized story, they risk compromising the integrity of the artwork itself. If the gradual stages of a Da Vinci painting or Michelangelo's sculpture were shown to the public, which of their choices might have been distracted from their own interests, instincts, and inclinations? Would this level of interaction be enough to disrupt an artistic thesis and distort the intention of a piece?

"The Da Vinci Code" was ridiculed by special interest groups because it had an albino killer; staying true to the story was seen as offensive for people with the condition. Why would anyone have to change a public display of art over a protest that's so absurd?

Who's gonna think he represents albinos everywhere?

Of course, comparing different types of art in a bit unfair. Movies want to develop buzz, while industry news doesn't cover the latest oil or marble purchases of modern painters or sculptors. A major tv show can run over 9 months, 4-6 of which could be months where filming is active and changes can be written into a plot or character arc. How much influence should an audience have?

Arthur Conan Doyle enjoyed great success for his widely-loved mystery series. He was lucky because he received this adoration in his own lifetime. Yet his fans were a bit too obsessive; every effort to write something different was drowned out by Sherlock Holmes fanatics. No one can know if he could have written the first stream-of-consciousness novel... But do you think he was satisfied as an artist? Do you think he deserved that satisfaction, no matter what? Would you say he should've stuck to Holmes if his other novels weren't "good" enough?

It's a little embarrassing to consider what right any of us has to complain. But I don't need to go that far into general artistic theory.

I think a film or tv audience really has "open season" for criticism when they're not dealing with a real artist. Shows like Entourage are an endless recycling of the same inept and immature premise (shallow life-porn for "dudes"). Series like Nip/Tuck become like a random curse word generator, a madlibs-style narrative that hunts for the "sexiest" or nastiest idea possible to throw at the crowd.

Other efforts, like "Sex and the City," "The Sopranos," and "Desperate Housewives," start with a premise that is soon abandoned in order to focus on the most popular elements. "The audience loves it when our guys invent really foul curses!" "Fans love the way that woman gets into fights with every woman around!" "When these likable-yet-different characters have a shallow-but-energetic conversation, viewers repeat the dialogue in offices all over America!" Ugh.

Does there have to be so much predictability? Does a show have to recycle the same moments or themes until it resembles self-parody? Does the repeated running time of a show mean that creators should be allowed lots of "dead space" to fill with popular repetition?

Because it can weigh in at 22 hours per thematic premise, TV is the best audio-visual art at developing literature-like depth. Whether you're talking about Mamet or George Bernard Shaw, no one wants any of their plays to have a twentieth sequel. I still want to stick to my own theory that you can determine the quality of tv series by asking if (a) the show had anything to say (so not Bad Boys II), and (b) if it said that in a good way (Gattaca, Pulp Fiction); then you also ask if you really feel cheated as an audience member, by either (c) general good taste (Gilligan's Island was stupid) or (d) the standards of what you're watching (mystery films have decent-to-good mysteries). It takes a while, but you start to understand how you can justify saying you saw an objectively bad film, character arc, tv season, or plot choice.

TV and film were virtually made for this level of exposure. They try for a level of attention that forces them to be dependent on the response they receive. Is it even a good idea to let the audience steer the ship in this case?

Critique is a constructive effort at improvement. Ideally, it's self-less. Outright criticism isn't bad - it can highlight valid errors, self-indulgent creators, and subtle flaws. Some artists' works are experiments in seeing how the audience responds, or figuring out how best to express an idea that will be understood the same way by the largest number of people. There, the audience is both valuable and necessary. Negative feedback can be juts as valuable as the positive kind.

Unfortunately, something like a movie costs a lot of money. I can think, offhand, of four films that are "perfect" and "cheap" - "Bad Taste," "Primer," "El Mariachi," and "Clerks." The slightly-confusing brilliance of "Primer" cost 6 grand; film stock took up most of the budget for this effective, stripped-down, masterpiece. Filmed in Mexico, "El Mariachi" cost 7 grand, and is packed with everything a pricey action thriller would have - Robert Rodriguez has his flaws, but he's a genius. The same goes to Peter Jackson's "Bad Taste" ($25k + $255k 4 years into filming).

Other classic low-budget films come in high compared to the rest. Yet the increased price tag makes you think even more about the risks taken by the creditors. "Clerks" cost $28k, just to show talking through 4 locations and one driving scene. Some "classic" choices: "Halloween" budgeted $250,000. "Napoleon Dynamite" less than $400k. "The Blair Witch Project" weighs in at $600 grand. My beloved "Brick" cost $450,000. Nor are tv shows much cheaper, I suppose. Those numbers represent a lot of people who have to wonder if they'll even make their cash back.

And yet Troma did such a good job with what they had.

Your standard American picture with one or more recognizable actors is a $10+ Million dollar bet. The game-changing DVD and online markets have skewed the results, but studios have good reason to want to release the best "art" for the buck. In our modern times, you'd think that the best stories would be the ones that actually make it through the process of approval and production. The film industry is run by financiers, and so box office gross is usually the greatest concern.

That fact alone - $="more!" - validates, or even requires, a lot of critical reaction. The widespread Hollywood ailment, sequel-itis, demands it. Consider "Shrek 4," "Clash of the Titans 2," "Resident Evil:Whatever," "Saw:Plot Torture," and "Final Destin-3d-10zz-ion." This is especially true when the after(wide-release)market can bring life back to "Futurama," but validate "Simon & The Chipmunks:The Squeakquel." I wouldn't be unkind about this if it didn't create: a chicken-and-egg problem where nothing is ever even somewhat new or original, while anything that actually is new quickly gets "franchised" to death.

Because you wouldn't sell tickets if you just gave a new title to an unrelated "sequel."

I can say so many things to validate the positive and negative aspects of "the audience" - it's certainly easy when I'm restricted to film. But since I began by thinking about long-form story-telling, I should return to it. After all, my original thoughts are not best applied to film franchises that take years to release. Television generally operates on a 2-4 month delay between the audience reaction and new footage that can respond to it.

I guess you could look at one worst-case scenario of fan-gratification: "MacGyver" producers banned love interests for the lead in order to gratify viewers. This meant that a single, well-off, good-looking genius in LA only had ex-girlfriends - except for that one episode where he got a girlfriend and she was evil. Romance is a pretty big element to remove from 6+ seasons of a show, don't you think? "SNL," even in its various heydays, turned modestly-successful skits into tired, worn-out photocopies.

Although fans watch shows, they're not necessarily the best judges of artistic necessity. And that's excluding whether television producers respond to fans well. How can the average TV viewer know the philosophical and practical ideas of art? How many know the main hallmarks of Impressionism, or French New Wave Cinema? "Gilligan's Island" was a hit even though critics thought it was moronic.

To almost-but-not-just-yet return to where I began, the public attention given to the conclusion of "Lost" highlighted the broad and massive extent of unrealistic audience expectations. For the love of heaven, the fan reaction itself became the story! I think many fans ignore a basic rule that is the very heart of my essay: In long-form story-telling, you can't expect a resolution or explanation for every "thing" that's mentioned.

The Problem With the Problem: The Audience Can Expect Too Much

You tell people that they're in a fantastical place where the impossible becomes fairly probable. You make up a magical vortex that transports things without ripping them apart. Creatures that can't fly in reality, like horsies, can fly. People display unique talents and abilities. Once your story is 5 books along, or you've aired 100+ hours of a televised show, you've introduced a lot of extraordinary elements. Why should any artist or author spend time explaining how all of them work?

George Lucas ruins the force by explaining it. Also, this device tests for it. Buy one now!

A one-shot film or show has little fat to trim, but it's different with a 3-picture series or 4th season show. Explaining it all is tedious and takes time away from other writerly pursuits. Little flourishes - a random character's great line, an unusual poster on the wall, a quirky joke or clothing choice - add a lot of life to long-form tales.

I have to think that devoting time to spelling out everything has many drawbacks. The first that comes to mind might be closest to my heart: can't it drain the audience's participation? If you answer every question raised by a piece, what is left for the viewer to do but absorb the information? If you don't know why a character limps, you spend time wondering what caused it. If you know why, there's less to think about, isn't there?

Is it necessary, as some OCD-esque attempt for utter narrative clarity, to explain how a magic carpet flies, or the workings of the magical bricks in Dialog Alley, or the scientific principles behind any working laser gun? Knowing how something works doesn't always improve your enjoyment of it. I imagine it's more fun watching a magic show if you don't know all the tricks.

No, seriously?

More importantly, how much fun would it be to watch or read those moments? When characters stand around describing things for the audience, it doesn't lend it self easily to compelling television. The right actors and situations can make that work, but it's quite a risk. In literature, it can be quite painful to read long segments devoted to exposition. So many words are used to portray the scenery or characters' thoughts. Can you really afford to grind the action to a halt so you can can explain how the Millennium Falcon flies?

Yet many viewers have enough time or interest that this is exactly what they'd like. If they can't get it in the show or movie itself, they'll buy books that explain how the Starship Enterprise is supposed to function. In these instances, success is really one's enemy, since you now have fans who are obsessed with trivial details or continuity errors that would be really taxing to address.

Other fans might not require absolute exposition (it corrupts absolutely, btw), but they do want any character tidbits to be fleshed-out and revealed. So some feel that if Indiana Jones says "Sala and I go way back," they won't feel content until they learn the details of their first meeting and subsequent adventures together. Satisfying those sorts of audience desires has several drawbacks: (a) it keeps the story rooted in old business instead of pushing forward, (b) it's predictable (must Indy always encounter snakes?), and (c) instead of allowing the writer to focus on telling the best possible tale, it burdens a franchise with supposedly-required elements. Some simply cannot bear vague references that require a little thought and guess-work.

Demanding to know what was done to polar bears on "Lost" shows bad priorities.

That last point is really important, since addressing all these things can draw a writer's focus away from the job of creating the current scene/dialogue/moment. An old critique of SNL says they prioritize the night's host or musical guest above making a funny scene. If you're writing comedy, then humor is the best benchmark - everything else is secondary, right? Just make it funny, and worry about the rest later!

Since resolution and explanation are about self-reference, look at the great 007 series. For all its successes, it displays inventiveness slowly drowned by repetition. Invariably, later entries in the franchise became welded to showing Bond's multiple lovers, visits with Q branch, a special watch, a special car... It was as if directors had no choice. All those elements eventually became distractions to writing and filming a good action/spy film. So it would go with any story. Moviemakers must do more than run through an artificial checklist of everything that comprises a James Bond pic.

Being so deeply compelled to repetition is a problem similar to excessive resolution and explanation. Both draw time away from the film's basic goals (e.g., good story + good image), and both eventually seem to involve a lack of creativity. Imagine a movie that gives a back-story to every character that appears in it. That wastes time. Or a 5th season tv drama that has a car chase in every episode. That's predictable. Or "Indiana Jones 6," that references many bits of every past entry in the franchise. That would be both predictable and a waste of time.

& It's "just not Indy," unless you say what happened to Marion, Henry Sr., and Brody, right?

Studio involvement is also a huge factor, since they don't see what's wrong with reminding movie audiences of "everything they love" about a popular character. In addition, movie executives are often scared that audiences will be confused or lost. Such excessive concern leads to a lot of needless hand-holding, or dialogue explicit to the point of being patronizing. This is why you have film characters that say the same thing in 3 slightly different ways. Or have awkward exchanges that completely describe a past relationship, instead of playing it through emotional expressions and hint-laden lines. Or feature a Bruckheimer scene that shows the outside of the J. Edgar Hoover Building and includes, at the bottom of the screen, the words "J. Edgar Hoover Building - Washington, D.C."

Extra Baggage: The Curse of Success?

I've covered some of this before with James Bond, and yet... Isn't an Indiana Jones film an archaelogical action movie set in the early 20th Century? Yes. Is it about a hat, a whip, Marcus Brody, Sala, the Ark, snakes? Hell no - those are merely elements that are associated with the first time an audience was introduced to Indiana Jones. If you removed each from a script with Harrison Ford searching for treasure in the catacombs of Occupied Paris, you might have one thrilling tale of Dr. Henry Jones, Jr.

In fact, here the intellectual extreme might be asking if an Indiana Jones sequel has to have a fistfight. Considering its genre, a brawl fits the theme. And it would feel like a pretty tame or odd action film without one... Consider other "obligations" - should Indiana Jones chase ancient supernatural treasures, or cyberpunk hackers, or even extra-terrestrials? I think you can answer that question for yourselves...

Keep in mind that these "money-grubbing mistakes," as made by media-producers, have some logic to them. If your movie was popular, it's because people like "X" story and/or "X" character and the things they did/saw. When every test screening and film critic applauds your ferris wheel chase, you're not a hack for thinking an amusement park showdown could fit into the next franchise entry. In the 00's, Japanese horror was a hot new subgenre in the US. Who knows what the next craze will be?

Apparently nothing says "terror" like pale, unkempt girls...

This knife called "Popularity" also cuts the other way - if three horror movies under-perform in a short period, it becomes harder to finance any scary picture for a while. The response to a script pitch might be, "No one's doing japanese horror these days," or "no one goes to see suspense now." And if "Goldfinger" had bombed, we may never have seen "You Only Live Twice."

I won't ignore the fact that, no matter what, the very act of making a theatrical sequel or 2nd+ tv season is a public announcement: you loved this, so now you're getting more of it. But I want to return your attention to these problems of repetition - this approach leads to inferior results, and gives less reason to make a sequel/spinoff/remake/what have you.

If "Toy Story 5" is just a slight retelling of "Toy Story 1," then the producers are abusing the audience. Sucking money from people twice for the same project (outside of Anniversary Releases, perhaps?) means that the competitive film industry is not working properly. Also, such a barren new release represents $70 million dollars that wasn't donated to the homeless or charitable causes.

So This Is What It's All About?: Indy's Hat is as Important as Indy Himself?

To my mind, when these repetitious elements pop up, there are a few probable reasons: (a) blatant efforts to improve success by audience-gratification, (b) some "things" become over-associated with the lead character or story, (c) the artist's laziness/low creativity/lack of opportunity. They can appear separately or together, though I think you can often find "weakness in numbers" on this topic.

In the last case, some directors are assigned to projects that they don't "fit" well. Or they just do a basic and decent job, then call it a day. Or they have influential people around them who interfere (aka, "The Alien 3 Studio Hell Apology"). In some instances, it's hard to find any fault in the artist. If MGM won't let you make a 007 movie without at least 2 "Bond Girls," then there's no alternative.

I feel that reasons (a) and (b) are so often connected that they're almost necessarily-related. Even if one doesn't exactly require the other, this statement holds up: When people overly-identify objects and "stuff" with a franchise, the audience and producers engage each other in unneeded identification and gratification. It's just not "Bond" without a Walther PPK and slick car. It's not a "Scream" film unless the villain trips/stumbles during the chase, or someone makes 423 "pop-culture references."

Those stupid helmets are official Jedi training gear, apparently.

But a spy might use many types of weapons, and some might not be practical for every mission. Some parts' hyper-aware pop culture references have no place in the film they appear in (Mike Myers' "The Cat in the Hat," anyone?). When I was a child, I liked Indy 3 far better than I did the 2nd film. On my first adult rewatch, I swung the other way hard - I have greatly-renewed respect for a sequel with all new locations and adventures, one where the lead is the only returning part. The series isn't called "Indiana Jones and His Amazing Friends," is it?

That first sequel kept many things from its predecessor. "Indy & tToD" includes upscale "creature gore" like the first film, but it has bugs instead of tarantulas and snakes. It is repetition, but you can say it's thematically appropriate to the supernatural B-movie nature of the series. "Temple" features a love interest, but the hero is an attractive man. At some point, relying too strongly on such familiar elements is a weakness. Imagine if "Temple" had a scene where Indy tells Short Round all about his successful Egyptian friend, Sala. That would be cheap and self-referential servicing of the fans. Also, it would probably stand out as a really awkward scene, because it wouldn't relate to the rest of "Temple of Doom."

Clamoring for Sprinkles

In brief terms, audience-appreciation moments are not an ice cream cone but the sprinkles on top of the ice cream. You can't call it a cone if you've left out the shell and flavored frozen milk. Or try it the long way: Artists can't give an audience more of what they like if it genuinely disrupts the artist's process, or clashes with the nature of their artwork. A conscientious person might add these touches if everything the piece needs is addressed.

It's true that a bullwhip distinguishes Dr. H. Jones, Jr. from other action heroes. But in the end, the fact that this man carries that object is more important in what it says about the guy than the bare fact that he actually has a whip. That whip means that Jones has a rugged, non-lethal weapon with some practical non-combat uses... It might be different if the first film were called "Indy VI & The Lion King's Lair" - but, in fairness, it would seem to suit such a tale.

Wouldn't you agree that it makes sense for a spy like James Bond to have access to high-tech gadgets? Does this mean that gizmos must be grafted onto each film, that he has to have one all the time? That you film some scenes just to display a special watch and car for each 2-hour movie? Having to spend hours writing and producing such scenes - much less adding to a film's limited running time - distracts from the true goal of making a good film based on Ian Fleming's character.

This preposterously "invisible" Bond car got three whole scenes!

The dull and inferior 2000 "Get Carter" remake includes scenes with Michael Caine, the lead from the original. All that time and energy would've been spent better making a decent, possibly-unrelated, movie with a compelling story and roles. All four "Alien" movies spend lots of time showing a group of people getting picked off one by one. After "Aliens," though, the development of the minor roles has evaporated; so too evaporates audience investment in the actors... So much screen time goes to utterly unimportant parts dying - but that time could go to humor, story, characterization of "real" roles...

Yet everyone wants "the cool scenes," don't they? They want those scenes that theater-goers and tv-watchers rave about for weeks. People watching a film want the hot sex scene, the cool gadget moment, the big explosion, the thrilling fight... Those things are parts of a movie - not the whole point of the picture itself. You can't tell a story with just those elements, and you should be thoroughly ridiculed if you try. Yes, we all want sprinkles or chocolate chips. What's the point if they're not added to a well-made ice cream cone?

People on both sides of the equation need to stop confusing the toppings with the whole treat. Ultimately, artists and audiences would be best served by a good sequel - quality is far more important than a popular element/motif from the first two offerings in a film franchise. Hell, everyone would be better off if 20th Century Fox approved "Alien 6: This Time It's Musical." At least it might have a chance of being distinguishable from the other 5...

Does Success Inspire Complacency? Lost, Star Wars, and...

When there's a new Star Wars film, it's basically review-proof. I've long felt that something that's already so terribly popular can probably save a ton of money on marketing. James Bond films are a good example of that. Many folks will go to see a new 007 entry, and it doesn't matter if there are a few large billboards in town; or even if it has tv ads playing every hour. In the case of SW, it may not be a waste, as they clearly want to sell a lot of ancillary products (toys, games, costumes, etc). I still claim that "Avatar" wouldn't have needed to spend much on spreading the word, given the abundant media attention garnered by (a) such an expensive film and (b) James Cameron's movies.

I want to be careful in how I mean "complacency." Obviously, a lot of people work very hard to make movies happen. Every poorly-received "The Last Airbender" had plenty of camera crew, fx designers, and sound personnel who worked quite hard to get the project into theaters. Even actors get a one-sided view of nothing more than their individual scenes. Few of those could be blamed for the lack of good dialogue or plotting - they weren't in charge of any of it. I can only imagine that many editors have tried to "salvage" awful footage in order to turn in a coherent crowd-pleaser - yet they aren't responsible for the film's flaws, they can only put the filmed material in the best possible light.

Tim Burton didn't drop the ball here, he chucked it into a black hole of suckiness.

Yet you know where to put the blame when you look at films by Michael Bay, Tim Burton, James Cameron, Christopher Nolan, Jerry Bruckheimer, Brad Bird, and George Lucas. These folks exercise a lot of control on the quality and content of their movies, and they are (by and large) free to make it as dumb or smart or dull or exciting as they like. Whereas David Fincher's "Alien 3" was tortured by Fox' restrictions and demands, the folks I've just named seem somewhat studio-proof. I'm sure they feel pressure to succeed and do well, but they've earned enough clout and respect that they have a lot of freedom. If "The Phantom Menace" had a boring or senseless plot, it's George Lucas (and his closest executives) who let it be released with a boring/senseless plot. Worse still, it's George Lucas who thought no one would (a) notice or (b) care. "Hey, look an explosion!" "Ooh! A lightsaber!"

But when properties are "hot" or "big," that past success can probably lead to freedom that borders on laziness. Most fans and critics thought that "Sex and the City 2" was a disaster on nearly every level. Didn't the film-makers want to make a great picture? Surely, they wouldn't want to damage their chances to make another sequel… But when you release a heavily-advertised PG-13 re-make, you know that it's open to the widest (and most lucrative) audience group; you also know that you're guaranteed certain ticket sales because your release is based on something of which the public is already aware.

So why isn't there better writing in major releases like "Attack of the Clones" or "GI Joe" or "Resident Evil: Infinite Tax Crisis?" The snarky answer is that "PG-13" is a special rating group filled with humans who don't care about things like "sense" or "quality." Ignoring snark, I have to think that the major players (directors, writers, executive producers) usually assigned to these types of projects are people who don't pay attention to things like dialogue. I also have good reason to assume that many folks ignore dialogue, et al, because they anticipate a certain degree of success with or without a quality story. It's not that Michael Bay couldn't get a fine story or words into "Transformers 2: Electric Boogaloo," it's that he simply didn't care, and its guaranteed $400M+ success supported his (and the studio's) apathy.

Well, no one cared about plot or character the first time, and that made $, so....

Since this article was inspired by the "Lost" finale, I'll add some brief thoughts into how "complacency" fits into that ABC TV show. That final episode was full of solid emotional beats and well-written moments. However, we're talking about a series that introduced magical pods that can manipulate time, a lighthouse that can show the lives of distant people, and a creature that is a moving column of black smoke. When it came to magical and mysterious objects, "Lost" really was an "everything but the kitchen sink" kind of series...

Most of the Island Mysteries were left unanswered, and that's ok - to a point. I can't castigate the series for focusing on the characters, because they are the most important part of a show. Yet the lack of attention given to the other elements actually implies that they were all completely unimportant.

Well, why was so much time and so many lines spent on these things if they were utterly irrelevant? It's almost insulting; don't distract me with shiny objects and then say they don't need to be addressed at all. It suggests that the writers had some flashy ideas, but nothing to back them up - nothing to lend meaning or relevance or some non-plot-device purpose. And I don't appreciate when story-tellers promise so much more than they can deliver. Most importantly, I think there would have been less "huh? That thing happened? Aw, never mind..." if the show hadn't posted such high ratings…

How does this Lighthouse show the future? It's broken quickly, goes unmentioned...

Simply put: people creating a small, under-exposed show are pretty likely to say "well, if we don't make Tom's character arc any good, or say why Sally needs that briefcase so badly, then the viewers will feel so let down that they might not tune in next week!" Folks working on the 3rd season of a runaway primetime success know they'd need to drop the ball for several weeks before their numbers dip from 2+ million to 1.8 million. With reality tv, producers see great ratings on mere spectacle and melodrama. How many seasons did "Heroes" have even though they were regularly ridiculed for atrocious plotting and scripting? (answer: 3 awful seasons that followed a good first season)

Let me turn back to "Lost" one last time, for what might be a mini-rant with a point. There's a part named "Hurley," and he has problems - he was been plagued by severe bad luck (meteorites, death, fires), and later committed himself to a psych ward over guilt. After a while on "Lost," he starts Seeing Dead People. Later still, he is back in Los Angeles, and gets into a cab with a mystical-magical man who has mystical-magical knowledge about Hurley's problems. In a trite little moment, the m-m man tells Hurley that he's not crazy; m-m man goes on to say that he's looking at things the wrong way, that seeing dead friends is a gift. It's cute and sorta touching, and the point is fairly valid.

This entire conversation ignores the fact that, about one day ago, Hurley was held in a police station for reckless driving and resisting arrest. Why? He saw a dead pal and drove away at high speed. So he ran from his gift, right? But in the interrogation room, Hurley looked at the 1-way mirror and saw the freaking island instead of his reflection, and then the glass broke and the room filled with water and he was screaming and then it all went back to normal in an instant. What the hell caused that, and why? That's not related to his visions of the departed, is it? Who wouldn't think they're crazy when first they see the Dead, then also begin having non-Dead audio-visual hallucinations?

I guess Hurley's "here's your deal" exchange was just a cool scene to broadcast, and the audience shouldn't ask... No, I can't finish such a stupid sentence. There was a need to address Hurley's near-drowning non-Island non-Death vision, but the writers felt it was purposeless... However, if that were so, the show should've dropped the flash-flood scene, right? Or they could have just done it right and addressed it in that moment where Hurley learns to accept his talents. I just don't wanna get jerked around by a senseless stream of cool moments, because a toddler could come up with that...

The writers on this show really were half-jerks...

In Conclusion

When I watched a good-but-oddly-disappointing series finale, I wondered if shows need to get worse the longer they stay on air. I had to ask myself if it's ever possible to satisfy an audience, and what sort of things threaten the quality of a project. These sorts of questions made me consider more problems relating to the effect an audience has on creators, and how creators can undermine their own efforts.

The time I spent thinking about this has given me additional perspectives that I didn't have before. I think that there's a growing confusion special to the modern tv series and film franchise. The confusion lies between which of these two things is "best": whether audiences should be catered to and whether not catering to them will result in something that is still "good." A common example of catering to an audience is seen in most any call-back in Film 2 to Film 1. The worst example is probably the sequel with nearly the same plot as its parent (e.g., "The Two Jakes" and "Chinatown").

But art, commercial or otherwise, works best when it achieves the basic requirements of its goals. A play is written as a series of dialogue exchanges set on a stage, while a movie is an audio-visual tale. If you make a suspense thriller, you must write and film something both suspenseful and thrilling.

Although media-producers often pander to boost ratings, the confusion is growing greater. This is partly due to the Internet, an open forum for grievances and congratulations where some grievances are tremendously petty, ill-informed, and trivial. The fact is that artists have a certain responsibility to reward the public for its attention. Yet concluding every little mystery, tying each loose thread, answering all questions that arise - that level of "fan service" is more likely to make projects worse. Distracting artists from the main goals of their works will often diminish the results of an artistic labor, to my mind (as both a writer and photographer). It might seem harsh to punish an artist for a lack of explicit detail or extreme exposition; it seems far worse to reward an audience for being too lazy to use its imagination.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Chime in!