For the past ten years, Quentin Tarantino's cinematic output has been focused entirely on revenge fantasies. Over the course of five films (four, if you count Kill Bill Volumes I and II as a single film) Tarantino has explored revenge across multiple, pulpy genres (including the Kung Fu flick, the war film, and the ultraspecific 1970s/80s muscle car movie mini genre) taking on the natural urges for payback felt by wronged contract killers, Jews during the Holocaust, and the female victims of sexual predators.

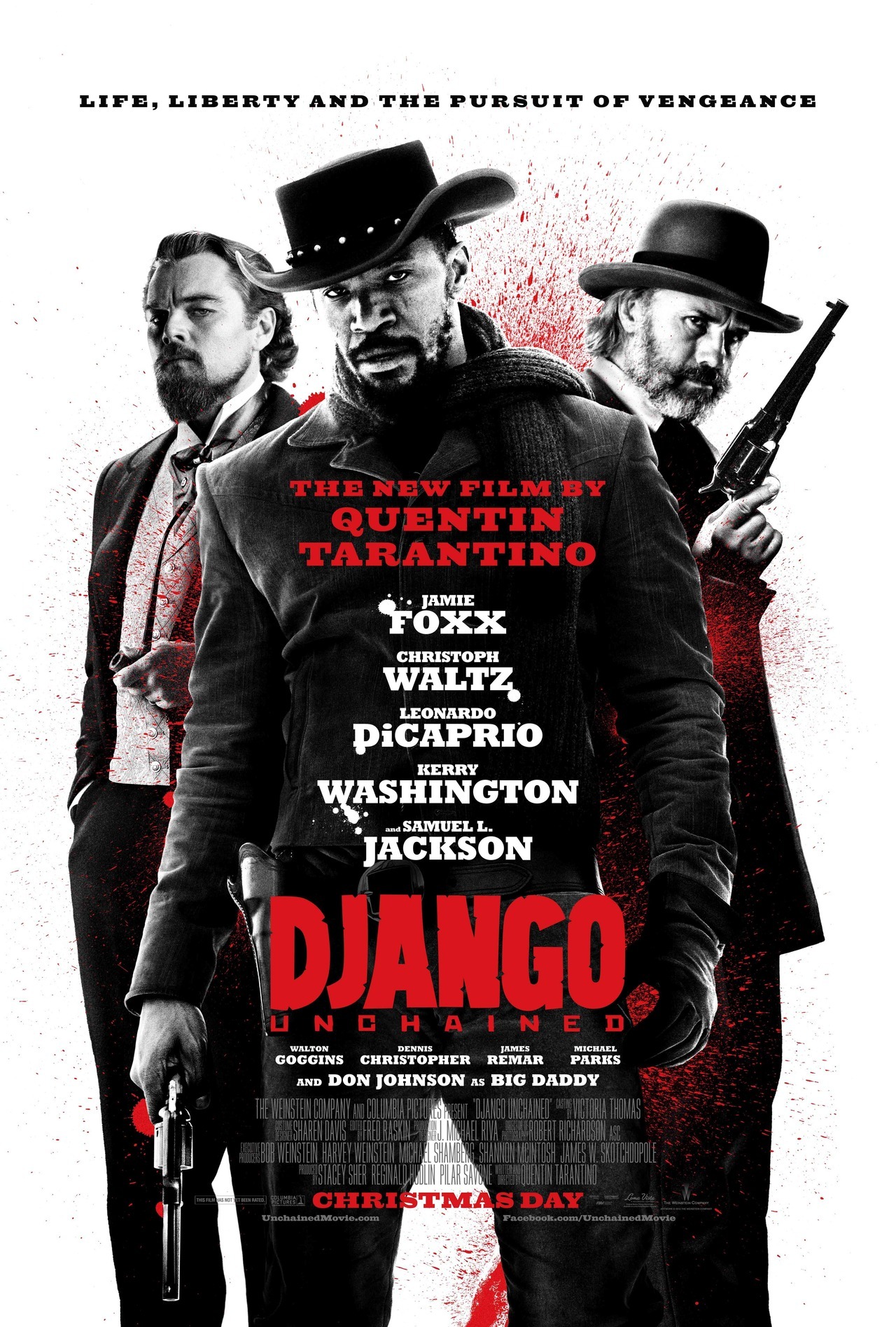

Tarantino's latest foray into the revenge milieu is Django Unchained, a pre-Civil War Western/Blaxploitation film set against the backdrop of Southern slavery. Like the other films of Tarantino's revenge period, it's not for those weak of stomach or short on patience. But amid the stylish gore and slick modern musical cues, Django actually has some interesting things to say about slavery and filmic revenge.

Stepping back for a second, here's the setup: Django (Jaime Foxx) is a slave who tried to run away from the plantation with his wife, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington); they were caught and separated. When we meet him, Django is on a hellish journey west across a frozen wasteland, on foot and in chains. He is soon found and purchased by the aptly-named Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz), a German dentist-turned-bounty hunter. Schultz has sought Django out because he needs the slave's help to secure the bounty on a group of miscreants called the Brittle brothers. Django needs Schultz's help because Broomhilda's still in bondage back in Mississippi. It looks like the beginning of a beautiful friendship...

As Django comes under the tutelage of Schultz and learns the bounty hunter trade, the film wanders close to the cinematic trope of "movies about black people that are actually about how awesome the white people who help black people are." However, the dynamic between mentor and pupil changes when the pair venture to Mississippi to wrest Broomhilda from the grasp of sweettoothed Francophile Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio).

While Django's hardened to the ugliness of the system in which he's lived, Schultz is shaken by the casual horrors they find in the heart of American slavery. At times, Schultz seems like a stand-in for the director himself. He starts the story somewhat resembling the popular perception of Tarantino's filmmaking style: a stylish psychopath with an inappropriate sense of humor who kills without compunction or remorse. However, as the story moves along, Schultz is humanized. We see him be moved by Django's romantic quest to save his wife, and he's also morally repulsed by what he finds on Candie's plantation. Waltz, who's been nominated for Best Supporting Actor for this role, does a brilliant job of showing the indignation boiling behind Schultz's eyes.

DiCaprio, who was originally sought to play the role of Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds, makes an excellent foil for Waltz, who won an Oscar for that role. Candie's a vile creature, whose pretensions toward sophistication only emphasize his ignorance--for example, he loves all things French, but can't speak the language and doesn't want it spoken near him, other than insisting that people call him Monsieur Candie. Ultimately, however, Candie's not the film's true villain. That distinction goes to Stephen (Samuel Jackson), the head house slave on the plantation. Despite Candie's phrenological musings about the mental capacities of slaves, Stephen's clearly the brains of Candie's operation. Playing against type, Jackson flips effortlessly from shucking and jiving at his master's side in public to soberly calling the shots in private.

Against these electric supporting performances, Foxx's lead is capable, but a bit bland. Django strikes the right tones as a blaxploitation super hero: he's athletic, a prodigy with the pistol and rifle, and he looks good beating a plantation overseer with his own whip. Foxx also does good work with early scenes in which we see Django's anguish and frustration with some of his limitations as a slave. But in the second half of the film, while Schultz's character gains depth, Django--like many blaxsploitation heroes--stiffens into the posture of the glowering badass.

Still, that's nitpicking--Foxx does a fine job, as do various supporting characters like Don Johnson and James Remar in roles that range from grotesque to extremely humorous. The film's real problem areas are the same ones that usually bedevil Tarantino's movies. At 2 hours and 45 minutes, Django Unchained is "don't drink a large soda" long. As Thaddeus noted, the n-word is used a lot (though not gratuitously, based on the context) so if that's a dealbreaker for you, best to stay away.

The biggest problem, particularly with this movie arriving in theaters so close to the tragedy in Newtown, is Tarantino's use of violence. Over the top violence has been part of Tarantino's tool kit since Mr. Blonde tuned his radio to K-Billy's Sounds of the '70s (link NSFW), but since Kill Bill, the ultraviolence has often been cartoonish. True to that tradition, the violence in Django Unchained ranges from the deadly serious to the absurd.

In the film's many, many shootouts, the gore is turned to 11--it looks like Tarantino buried every squib inside of an overripe tomato--and the violence is often supposed to be comical. In Inglourious Basterds, this approach of comic overkill worked better because the Nazi "bad guys" were often humanized before they ran into the buzzsaw of revenge. There is no equivalent to Max, the German soldier whose wife just had a baby, in Django Unchained--no suggestion that the audience should do anything other than enjoy the carnage that Django and King Schultz wreak on the wicked. Without that moral ambiguity, the cartoony violence in Django Unchained becomes numbing, and by the end, there were times that I thought, "C'mon, just kill him already!"

What Tarantino loses with his lack of sympathy for the slavers and their racist toadies, he makes up for with his focus on slavery's victims. On a visceral level, Django Unchained makes you feel the horror and the human cost of slavery like no movie I've seen before. The first time we see a character lashed, the scream is bloodcurdling and the camera holds us close up on their face. There is nothing cinematic about it. Later, Mississippi is a Hell on Earth, where slaves are forced to kill each other in brutal Mandingo fights, males are castrated, and runaways are chased up trees by vicious dogs, and--if they're lucky--tossed in the coffin-like hot box.

It's a horror story that can only be told with Tarantino's flair for violence, his taste for the distasteful. The ending of Django Unchained falls apart a little bit as the fantasy spirals out of control, but the movie overall is highly recommended. It's not as good as Inglourious Basterds, but I say that knowing that my appreciation of Tarantino's recent movies invariably rises with subsequent viewings; I look forward to rewatching this one.

This is a great review, DJ! You very neatly dealt with the issues of QT's relationship with violence, and how he has a very narrow emotional focus that he wants to convey to the audience. That latter point is really special to me, because I've had a hard time trying to articulate it without resorting to the old "he's just like Spielberg, his movies are emotionally-manipulative" line.

ReplyDeleteThis was a very good movie, and I do look forward to seeing it again. That said, I've already started to think up a few problems with the narrative (one is definitely logical, the other is more narrative convenience than logic - I'm just not sure whether I should fire away here or write a little douple-dip on the pic...

A double-dip with spoilers would be good, since there's a lot to discuss that can't be done without really getting into the film.

DeleteArgh! I'll try, I'm just still trying to sort out my feelings about the picture. I already have several good points to make, though, so maybe it won't be too hard.

DeletePS, I forgot to mention it, but you choose the perfect moving gif above - nice!